It’s the OpenSim Community Conference this weekend. I’m not presenting this year but thought I’d post this as a token of the booth that accompanied last year’s talk before I tear it down.

It’s the OpenSim Community Conference this weekend. I’m not presenting this year but thought I’d post this as a token of the booth that accompanied last year’s talk before I tear it down.

Reminded of the Different Trains performance I attended EIGHT YEARS AGO at historic (1836) Edge Hill Station. The composer, Steve Reich, made a brief appearance at the end. Bill Morrison’s specially compiled video, some of it partially degraded, added a lot to the overall effect, plus the passing of actual trains. Delighted to find video of the performance which gives some impression of what it was like being there. A little more background from Parr Street Studios on context and pre-recorded elements. The BBC report also has brief footage.🎵

No idea where those eight years went.

In the summer of 1834 an innovative moving panorama of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway called the Padorama was displayed in the Baker Street Bazaar, London (see Part 1). The exhibition there was not, however, the end of the story. As Richard Altick (1978) first described, the Padorama unexpectedly saw a second lease of life in Brooklyn.

A move to Brooklyn, Long Island

An unknown purchaser supposedly paid $30000, the equivalent of $1M at present day values, for the Padorama in London and shipped it to Brooklyn, Long Island in the USA. If this figure is accurate it presumably reflects a very significant financial transaction. However, neither the vendor nor the purchaser is known, nor what exactly was bought. Did the purchase simply cover the twelve images or did it include the foreground, trains, mechanism and steam engine? It seems unlikely (but not impossible) that the rotunda was shipped as well.

Guillen (2018) has provided a detailed analysis of Frederick Catherwood’s panorama business from its inception in 1838 to its fire-associated demise in 1842. The six static panorama paintings he purchased from Robert Burford cost $1000 each. Burford had cachet not dissimilar to Stanfield and unless a premium was being paid for the models and machinery it is hard to see how the Padorama could have cost more than $10000, possibly significantly less. However, as we shall see, the cost may have included the services of an engineer to assemble and maintain the Padorama.

George Odell in his Annals of the New York Stage quotes the Star newspaper (presumably the Long Island Star) in announcing the display in 1835 of the panorama (I will also use the original name) in a specially built building 70 ft long. The same source mentions the size of the proscenium so it seems likely that this was a second purpose-built home for the Padorama and presumably rectangular rather than circular in layout.

It is unclear whether Messrs Marshall exported panoramas to the US and it is not known whether Marshall’s in fact owned the Padorama, their name being conspicuously absent from the advertising. Indeed, it may be that the sponsors of the production (I speculated that these, if any, might be the “Liverpool men”) retained ownership and undertook the sale. The identity of the purchaser is even more obscure and does not appear on advertising in the Long Island Star newspaper.

Indeed, regular advertisements for the panorama appeared in the Long Island Star but without mention of the proprietors' (NB plural) names. The panorama was described as being upwards of 20000 square feet with a railroad fixed in front of the picture. Trains run at intervals to provide “one of the most complete illusions ever attempted.” Opening hours were 3-9pm (it had been afternoon-only initially), entry 50 cents adults, 25 cents children, with illustrated book 12.5 cents. The admission price halved towards the end of the run when opening hours changed to 10-1, 3-9 and a note was added to the effect that an omnibus was available at Fulton Street at the top of Pierrepont Street, presumably connecting with the Fulton Ferry.

The change in admission price may have been an attempt to make the panorama more affordable and hence open to a broader class of persons as well as encouraging repeat attendance. Increasingly inclement weather may also have led to reduced attendance and a need for greater flexibility. Guillen (2018) reports that attendance at Catherwood’s panorama fluctuated considerably especially with national holidays and that his building was subject to temperature extremes, something addressed in part by the introduction of heating.

The change to proscenium format

The unknown purchaser apparently both changed to a lateral rather than circular format and increased the canvas size, supposedly by 50%. This may have included greater height (24 vs ~18 ft) as well as inclusion of additional views. How much of this was intended in advance is unclear but it presumably explains in part the launch delay which was nearer eight weeks than the two originally envisaged.

Huhtamo (2013) suggests that Marshall’s produced panoramas that could be used in either format. Muddying the waters slightly, he also observes that a proscenium might be used with a curved moving panorama.

Location in Brooklyn and its significance

The panorama was situated at the foot of Pierpont Street, presumably on the banks of the East River at the end of what is now Pierrepont Street named for resident Hezekiah Beers Pierrepoint. Street directories of the time show a panorama at the junction of Pierrepont Street and Columbia Street and a map of 1835 shows a large building, possibly the panorama, on the west side of Columbia Street directly adjacent to the bluff.

If indeed it is the panorama, its shape is consistent with a lateral rather than circular display although, of course, small curved panoramas were displayed in rectangular venues such as Spring Gardens, London. It is unfortunate that the depth of the building is not mentioned but plausible perhaps that a circular rotunda might approach perilously close to the bluffs.

Unfortunately, elements of the map look prospective. For example, Constable Street, later Montague Place, appears to run through the mansion known as Four Chimneys, the residence of the Pierrepont family and demolished in 1846 after HB Pierrepont’s death. Moreover, although Pierrepont owned land on either side of Pierrepont Street, land further to the north was owned by Samuel Jackson about whom little is known by comparison beyond the fact that there was a wharf on the foreshore which he rented to Hicks for the lumber trade. Nevertheless, this is a plausible location for the panorama.

Pierrepont only allowed brick buildings on his estate unlike that housing the panorama, another reason to suppose that it was not on Pierrepont’s land although, of course, this may only have been a temporary venue and hence an exception made.

The term Padorama did not cross the Atlantic and there are no references either to the mechanographicorama or disynthrechon although it is possible that these were retained in the books but not the advertising. These obscure neologisms were rendered in the US simply as “moving panorama” which presumably is something people understood rather than necessarily reflecting a change in presentation.

Motivation

In the absence of any hard evidence, here are some suggestions as to possible developers of the Brooklyn panorama.

Pierrepont

Around 1835 HB Pierrepont was attempting to promote Brooklyn and, in particular parcels on his estate, as desirable homes for people who would commute to the city by ferry. Accordingly, the panorama might have been conceived as a means of attracting people to visit the location, a pleasant spot for a walk in any case. However, if the panorama is outwith the Pierrepont estate then this seems less likely.

Pierrepont had a possible connection with the early panoramas in Paris via his friendship with the inventor Robert Fulton. However, the railroad was arguably of marginal benefit to his own enterprise and his family does not appear to have been involved in railroad projects at this time although available information is limited.

Railway interests

Another possibility, as in London, is that the intention was to promote local railways, the first on Long Island being constructed at this time. The Brooklyn and Jamaica Railroad opened on 18 April 1836 and ran from nearby South Ferry which provided a steamboat link to Manhattan. As with Liverpool and Manchester, no locomotives were initially allowed on the streets of Brooklyn and so the first part of the 11 mile journey to Jamaica was horse-drawn (it would later use locomotives in a tunnel). The line was quickly leased to the Long Island Railroad which continues in name to the present day and is the busiest commuter line in the USA as well as having the oldest name.

The railroad would likely have had direct or indirect contact with Liverpool. For example, it sourced its rails from there.

As in London, it seems unlikely that shareholders would sanction such expenditure so it might have been the act of a group of wealthy individuals connected to the project.

A cultural centre for Brooklyn

The Padorama might have been mounted by one or more persons seeking to promote some kind of cultural activity in Brooklyn and doubtless many of the better-off locals would have visited. However, this overall aim seems unlikely given the temporary nature of the exhibit and the relatively short run.

Vanderlyn’s ill-fated static panorama, the first in New York City, was sponsored by 142 subscribers who raised $8000 and it also benefited from a peppercorn rent (Guillen, 2018).

A panorama distribution company

Whereas Messrs Marshall initially both produced and toured their own panoramas, the trend since the death of their founder may have been to outsource the arduous touring aspect. However, this does not explain the sale of the panorama immediately after the end of the run unless, of course, there were financial pressures.

A relative of Samuel Jackson

Frederick Catherwood, who would later have a panorama building on Broadway, had a business partner or possibly agent called George W Jackson. Little is known of Jackson and the possession of the same family name may be coincidental but it is also possible that his relative Samuel allowed George to engage in some panorama speculation on his land free of charge for a short time before Catherwood’s arrival in the USA. There are both Samuel and George Jacksons in the Hicks genealogy but these are common names.

An entertainment entrepreneur

A final possibility worth considering is that this was an initiative by a New York panorama business hoping to cash in on the new railroad and summer visitors to the Heights as well as trial the technology behind the Padorama. A walk along the foreshore and a view from the Heights would make a nice weekend excursion for New Yorkers who might also be inclined to spend 30 minutes viewing the Padorama.

However, New York would be surely be a better location, plus the paucity of newspaper advertising beyond the Star is odd although perhaps adverts were placed on the streets and ferries rather than the papers. The delay in getting the show operational may have proven fatal to any long-term plans. As an aside, Pierrepont’s wife loved the area but complained it was mosquito-infested.

Last days at Brooklyn Heights

According to Odell, the Padorama closed in November 1835 but had provided the sole delight for his report in the autumn Star. The 7 January 1836 edition of The Herald announced that after a delay due to fire (at the auction house presumably) the sale of the Padorama (which it calls the Grand Moving Panorama of the Manchester and Liverpool Railroad) together with the building, fixtures and galleries (presumably tiered seating).

Manhattan transfer: Niblo’s Garden

An advert in the Evening Post provides a clue to the next stage of the Padorama story. The 13 July 1836 issue refers to “a grand moving panorama of the Liverpool and Manchester Rail Road, the largest in the world”, and the 7th October issue states it “cost in London 30000 dollars”. It covered 50000 sq ft (surely an exaggeration?), required a steam engine to work it (as expected) and was “painted by the best artists in Europe under the very celebrated Stansfield (sic)”. The location was Niblo’s Garden on Broadway. Advertising claimed it was the largest moving panorama in the world and that it had been assembled (and presumably maintained and possibly operated) by a Mr Hitchings who had accompanied the panorama to the US.

This high class pleasure garden owned by William Niblo opened in 1828 and boasted a theatre and saloon. It had shown two peristrephic panoramas sourced from Messrs Marshall in the early 1830s. Niblo’s Garden was not the only venue showing panoramas in New York but was a singularly large one that could if necessary accommodate another building on a temporary basis. Previous moving panoramas had been displayed in the saloon but presumably the Padorama was both too large and too loud. On balance Niblo’s acquisition perhaps argues against the involvement of any New York panorama venue in the Brooklyn venture or presumably the venue would have shown it themselves. Clearly Niblo also believed that he was serving a different audience to that in Brooklyn.

Initially the Padorama was open both day and evening but by October it was only open 7-10pm due to the expense incurred with the engine. Niblo’s Garden had gas lights in its garden so presumably gas was used for the panorama as well.

Last days

An advert dated 18 August 1837 indicates that a new moving panorama had been installed at Niblo’s Garden. Again, no mention is made as to the theme nor, unsurprisingly, the fate of the old one.

Assuming other panoramas had not been shown in the meantime, a year would have been a long time for a panorama to be on view in a single location, suggesting that it was popular despite the extra operating cost. Niblo’s Garden was a carefully crafted and somewhat exclusive leisure experience for middle-class New Yorkers with satellite hotel and in-house stagecoach. It seems unlikely that an underperforming attraction would be tolerated, even if not a headliner (fireworks were a major attraction). It seems reasonable to assume that the Padorama had merit even if the novelty of its subject had inevitably diminished over time.

Who bought the Padorama from Brooklyn?

The obvious answer is William Niblo. Niblo’s advertising on previous occasions had made clear that he had obtained a panorama at considerable personal expense. On the other hand that claim is notably absent in this case.

Another possible purchaser is English emigrant painter William Sinclair who had previously shown two of his own panoramas at Niblo’s Garden, one of which toured subsequently to Baltimore. Perhaps Sinclair rented space at Niblo’s to display panoramas he either owned or rented. Guillen’s analysis of Catherwood’s business appears to show that there were continuing monthly costs on the panoramas he had purchased for his establishment which was just across the road from Niblo’s.

Gaps in our knowledge and possible resolution?

How and why the Padorama crossed the Atlantic remains a mystery. Did an American see it in London and spot an opportunity? It seems hard to believe that it was bought sight unseen.

What was the cause of the costly delay in Brooklyn? Why was there a shift to a proscenium presentation and why was the canvas made bigger still? While it had use in marketing, a large canvas would be more awkward to transport.

At the other end of its run, what happened to the Padorama in summer 1836? Although static panoramas sometimes moved on to other cities on the eastern seaboard (Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston) there is as yet no evidence that this one toured any further and its infrastructure requirements would in any case have made that challenging. Perhaps it was a technological one-off, an interesting thing of its own time but ultimately an unremunerative dead-end once the railway revolution was in full flood.

One might imagine that the canvas itself would have become worn over time and rapidly deteriorated further in storage prior to ultimate disposal. The models, however, may have had some value and one can imagine their being cherished family heirlooms, at least for a time.

What is signally missing, however, is any record of pertinent lived experience of New Yorkers or Brooklynites of the time. Many will have kept personal diaries and some of these are available but not as full text that can be readily searched online.

Conclusion

For a brief point in time the Liverpool & Manchester Railway captured the global imagination and promised a step change in mobility that would have a profound impact on people’s lives, both at work and leisure. As Messrs Marshall would doubtless contend, the best way to experience its effect on time and space short of a visit in person was to watch it spool past on the Padorama, a technological (and artistic) response to a technological feat. The net effect was perhaps to go some way to making the railroad marvel more of an everyday experience at a time when it still elicited a degree of fear and uncertainty in some quarters.

The first modern railway, the Liverpool & Manchester, opened in 1830 and by 1834 construction of railways into London, notably the London & Greenwich, was already in progress. To accompany this seismic shift in mobility a moving panorama of the Liverpool & Manchester was presented at the Baker Street Bazaar in London between mid-May and early September of 1834.

It appears to have been based on images presented in a book, the Railway Companion, published the previous year and written by the somewhat cryptically named A Tourist with images credited to an obscure H. West. Most of the images recur in the Descriptive Catalogue that was on sale alongside the panorama, an exception being the picture of the Oldfield Lane cattle station which by this time had closed and moved to Charles Street adjacent to the Liverpool Road station in Manchester. The book by contrast omits the image of the Patricroft Tavern (now the Queen’s Arms) and Bridgewater Canal. Both omit images of Flow and Chat Moss deemed presumably of less artistic interest (these appear on a compilation panorama).

As ever, much conjecture and a work-in-progress. A talk on this subject with animated visuals was given at the OpenSim Community Conference 2024. Much background was derived from Huhtamo (2013) Illusions in Motion, MIT Press.

Sponsors and target audience

The lack of attribution carries over to the panorama itself. Somewhat atypically there is no company named in the copious advertising and no artists named beyond making general claims for their ability. Freeman (1999) has suggested that much of the artwork published alongside the launch of the railway was sponsored by the railway company and the same may be true of the Padorama. However, its cost would have been orders of magnitude greater and hence greatly displeased shareholders. It is possible therefore that the panorama was funded by the “Liverpool men” who were seeking further railway investment opportunities at the time or a similar group based in London.

If indeed it was the “Liverpool men” there may have been a degree of self-congratulation that their faith and investment in the Stephensons had been vindicated in the face of Parliament’s initial rejection. The Padorama may have been intended to celebrate the success of the railway while perhaps also attempting to assuage fears as to the future impact of its expansion on both town and country.

One unique feature of the Padorama was that it was displayed continuously, there being no set performance times. This may have increased footfall but may also have been particularly amenable to business people dropping in during a spare half hour. The venue, the Baker Street Bazaar, was aimed at the nobility and gentry and both groups may have been regarded as potential investors in future rail projects. The Padorama thus served as a (doubtless sanitised) briefing for those who had not experienced the actual railway or who had been exposed primarily via the newspapers to its adverse consequences in terms of railway accidents.

A final group identified in the advertising comprises juveniles who were encouraged to see the panorama as a mix of entertainment and education during their summer holidays. While there may have been an element of pester power intended here, it is also possible that the Padorama investors were targeting the engineers of the future.

Production company

While the vast majority of advertisements and reviews fail to name the production company involved, two sources identify Messrs. Marshall, a prominent purveyor of moving panoramas in the capital and elsewhere. Founded by the Scot Peter Marshall, the company was well-regarded and among its products was a very popular rendition of the coronation ceremony and procession of King George IV. This features in a satirical cartoon that reflects the high level of interest in moving panoramas at the time.

Marshall, however, died in 1826 and, according to Huhtamo, under Peter’s son William the company had largely (but not entirely) withdrawn from London. Moreover, the venue, Spring Gardens, whose entrance is shown in the cartoon had closed and been demolished by 1834. Nevertheless, something had enticed Marshall’s to develop the Padorama and it may have been both the sponsorship and the technical challenge as the Padorama had novel features.

Moving panoramas

Moving panoramas were in all likelihood diverse in terms of their viewer experience and (hidden) mechanics. At their simplest a painted canvas was spooled across a viewing aperture, a stage-like proscenium, from one spindle to another by two operators (“crankists”) manually hand-cranking. By contrast the Padorama, presumably by virtue of its size and continuous operation, required a steam engine which was likely in another room or building and driving the mechanism via a belt and pulley system.

Marshall’s were known primarily for their peristrephic panoramas in which the painted canvas scrolled in a concave arc in front of the seated viewers (Plunkett maintains it was convex). The word “peristrephic” featured prominently in their normal advertising but was notably absent from the Padorama coverage. The book and descriptive catalogue, presumably both from Marshall’s, talk instead of a mechanicographicorama delivered via a disyntrechon. This is, l assume, a reference to the other unique features of the Padorama, a moving foreground as well as moving trains.

The artists

It is possible that the sketches that appear in the book and catalogue were made by William Marshall or someone he employed (H. West perhaps) and the final versions developed at scale by a team of scene painters. Moving panoramas had become a popular part of many theatrical productions and their lead artists were sometimes named prominently on the playbill. It was a natural development when the same artists were engaged to develop moving panoramas for display in other venues.

Perhaps the pre-eminent scene-painter of the time was Clarkson Stanfield (1793-1867) and one source refers to the Padorama as having been painted under his supervision. This may, however, be a clever way of crediting his only student, Philip Phillips (1802-1864), who is named in a separate source. Phillips would have led a team of painters and, indeed, one source criticizes the uneven quality of the pictures as well as making more general comments about the unexceptional nature of the countryside between Manchester and Liverpool.

Stanfield was a resident scene painter at the prestigious Theatre Royal, Drury Lane where Phillips presumably worked as well (he later went to the Surrey Theatre). Stanfield quit the theatre over “creative differences” in December 1834 and at the same time largely retired from scene and panorama painting in favour of less arduous easel painting although he did occasional panoramas thereafter for friends. His involvement, if any, in the Padorama was possibly his last panorama.

The venue

The use of a Bazaar as venue was not unusual. Large-scale art had been displayed at Baker Street previously and Stanfield, for example, had previously used the Royal Bazaar, Oxford Street under the auspices of his British Diorama company. His large diorama of York Minster in flames was inadvertently set on fire by an operator igniting chemicals to give a red flame effect behind the canvas. Unfortunately this also led to the total destruction of the (well-insured) bazaar although Stanfield did display there again subsequently.

At Spring Gardens Marshall’s used the Great Room, presumably a function suite for balls and banquets, as well as the presumably smaller Lower Great Room. There was similarly a Great Room at the Baker Street Bazaar which was used for exhibitions, most notably Madame Tussaud’s waxworks from 1835. It would have had the ceiling space to accommodate a large canvas but it appears that it was being used for furniture sales in 1834.

Much of what we know of the layout of the Bazaar dates from later insurance maps. However, most of it was off-street, hidden behind shops and residences, one of which was converted to an entrance with a portico. Its origins, however, were as a barracks for the Life Guards, part of the Household Cavalry. Subsequently it became a Horse Bazaar (it was trading as such in 1833 under its new owner MC Allen, the previous one having gone bankrupt in 1832) and later still sold carriages and tack before diversifying still further into high quality home furnishings.

The central area was therefore presumably given over to stables surrounding a large parade ground and this may have been the location of a purpose-built theatre, albeit temporary and likely wooden. It is hard to imagine that the theatre could be anything but disruptive for the horse trade in the immediate vicinity and it is possible that some of the stables were vacated in favour of Mr Allen’s other establishment, Aldridge’s Repository.

It seems likely that the entrance to the former Parade Ground was via King Street at this time.

The theatre

One source cites a visit to the “Rotunda” in order to see the Padorama. Such structures were relatively commonplace (there was one on Bold Street, Liverpool built for static panorama viewing) and were typically cylindrical or hexagonal with domed or pointed roofs. Normally static panoramas were draped from the walls and viewers stood on a central platform half-way up the picture as specified in Barker’s original panorama patent. Lighting was typically via glazing in the roof. This was diffused by a canopy above the platform which also obscured the top of the panorama and the means of attachment. An analogous skirt at the bottom of the platform hid the base of the platform and possibly the flooring also although often there was a surround at the base which continued the theme of the painting and potentially had related artefacts scattered about.

Viewers would pay their entrance fee (1 shilling in this case, equivalent to about £3.50 now), optionally purchase a descriptive catalogue for the same price and then walk along a dimly lit passage leading to a stairwell either external or integral to the platform (the latter would presumably be the case here). As they emerged onto the platform they would immediately be struck by the brightly lit immersive image moving slowly before them.

In the case of static panoramas the diverging sight lines were centred on the middle of the platform which worked well for cityscapes seen from an elevated position (the top of the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral is a classic example for London). Whether circular moving panoramas were painted in similar fashion is unclear.

The paintings

The images in the Railway Companion book all have an aspect ratio of around 2.5. According to Odell, the proscenium in the New York version was 40-50 feet wide by 24 feet tall although it was noted that this was half as big again as the original 10000 square feet, the gold standard for value for money in terms of entrance fee. I am assuming that the images used in London were 45 feet x 18 feet, an aspect ratio again of 2.5. That makes a total of 540 feet in length and 9,750 square feet in area, close enough to the target. The complete performance took about 25 minutes so each of the twelve images was visible for about 2 minutes.

The images were distributed across the 31 miles between the two towns with clusters at Manchester and Newton-le-Willows and a solitary view at Edge Hill for Liverpool. The focus was on civil and mechanical engineering with viaducts, bridges and locomotives featuring prominently as well as the Moorish Arch and a distant view of the tunnels at Liverpool. All apart from the Sankey Viaduct (?) are north-facing and some are distant views while others are trackside. In modern terms the overall effect as the image passes would be of a slow-moving, heavily edited tracking shot showing the most interesting parts of the line (as the descriptive catalogue makes clear).

Some sources did remark on the exclusion of notable features such as the embankment at Huyton and the Olive Mount cutting. The skew bridge at Rainhill is also a notable absentee and there is no mention of the use of banking engines or indeed of the cable-hauling in the tunnels at Liverpool.

To display all the images simultaneously would require a cylindrical building with a diameter of about 170 feet which seems improbable under the circumstances. Based on the Liverpool Rotunda, a diameter of 50 feet, perhaps a little more seems appropriate given the site and temporary nature of the structure. This implies that Marshall’s must have had a means either of “compressing” the image, for example, by a serpentine arrangement of rollers, or else remove and replace images “on the fly” (something that US inventor Robert Fulton addressed for static paintings during his stay in Paris). All of this would take place out of sight of the viewer behind a curtain or partition. This is presumably the feat “men of science” deemed impossible in one of the sources.

Lighting

The original dioramas were lit by natural light with viewers in a darkened room. Stanfield, however, preferred gaslight and theatres had been generating their own supply in the absence of a public one. The Bazaar may have done the same given it too had been gaslit since the end of the previous decade. The decision to close at dusk/6pm must therefore have been for operational reasons such as site normal opening hours.

Some sources refer to diorama-like effects, particularly in the lane scenes. This may simply have been casting of shadows with shutters and coloured light created by interposing appropriate filters. One source comments that the season depicted was between summer and autumn (are those leaves being collected at Parkside?) so lighting may have been designed accordingly.

The classic diorama often depended on back-illumination in order for figures painted on the reverse to magically appear on the front through the thin calico canvas. Similarly the movement of a moon could be simulated with a candle in a tin can and water movement in rivers by rippling the canvas. However, none of this is possible if the canvas is directly adjacent to the wall as here.

Sound effects

One source comments on the rumbling of the train as it approached and the falling off of the sound as it passed. Whether this was due to the train, a deliberate built-in sound effect or simply the noise of the machinery moving the foreground is unclear. The proprietor claimed to have been worried that the sound of the trains would alarm people but this may have been showmanship.

No other sound effects are noted and there are, for example, comments regarding other diorama performances that nobody needed to hear the sound of water. Tremendous creativity was expended elsewhere in the cause of simulating reality but the continuous nature of the Padorama performance may have been a constraint.

Likewise, popular panoramas often had a musical accompaniment, possibly to hide the noise of the machinery. This too is probably absent.

Continuity

The images were presented in the order the voyager would have encountered them with a generic view of a locomotive, the atypical Caledonian with twin vertical cylinders, to mark the beginning. The first two views of Manchester are distance views but thereafter the perspective is roughly trackside until Newton and the Sankey viaduct (the treatment of Flow and Chat Moss is unknown) so there would have been plenty of opportunity to run the model trains along the double track during the middle segment.

Moving panoramas often depended on lecturers to interpret the image and entertain the audience. The continuous nature of the performance again makes this unlikely so the audience would have to read the descriptive catalogue for information which suggests the platform was adequately lit. However, according to Plunkett, Sinclair displayed a panorama in Bristol in 1829 that ran continuously from 10am - 10pm without mention of a steam engine. The topic, the Battle of Navarino, is likely to have required a lecturer so it may simply have been that teams worked shifts to cover the day.

The trains

A number of steam locomotives are shown on the paintings, including a close-up of Caledonian with its unusual vertical cylinders, one of many evolutionary dead-ends on what was a highly experimental railway.

Whether the trains were hauled by actual steam engines seems unlikely given both the potential fire hazard and the labour needed to keep them in steam. Huhtamo suggests they were cardboard cut-outs but sources indicate they were far more realistic and one must assume that as a minimum wheels were turning and smoke emitted from an appropriately contained source. Possibly they were pulled along by a discreetly hidden cable.

One viewer refers to the model passengers in open carriages as looking like “pygmies” which suggests they were of a small but appreciable size. Quite where the trains ran is unclear although a viewer refers to “looking down” which possibly implies they were standing (the norm for a rotunda) and that the trains ran close to the base of the painting (which might otherwise be obscured). On the other hand, other observers only saw the trains as they passed in front of them so they may have been (optionally) seated.

The moving foreground

This was a significant and appreciated feature but quite what it comprised or how it was implemented in a rotunda is unclear. Was the foreground image-specific? Did it convey a sense of motion parallax? Where was it positioned? Was the track (and train) on an arc of foreground with both moving together. After all, there was no sense in trains or track obscuring distant views.

Conclusion

The Padorama was likely an expensive and ground-breaking production. It is possible that Messrs. Marshall considered it as an opportunity to take virtual tourism to a new level as well as automate aspects of its performance. However, it is not clear that the scale and subject matter made it profitable as nothing on this scale was attempted again until the Paris World’s Fair in 1900.

In Part 2 I will describe what is known of the Padorama’s final years in the USA.

I first wrote this account in 2018 on the build2understand blog on 10centuries.org under the nom de plume ed3d. This version has not been further updated as yet. The markdown support also varies between platforms so there may be issues that need fixing. Please bear with me.

The Huskisson memorial at Parkside marks the scene of the fatal injury to Liverpool MP William Huskisson during the inaugural run of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway (L&MR) on 15th September 1830. It will be familiar to passengers on the Liverpool and Manchester line as a small building on the southern slope of the cutting just east of the A573 Parkside Road. Historic England describes it as grade II listed and as being in the form of a “simplified Classical temple” of painted stone. The date is given as 1831 but the story is probably a little more complex than this suggests. As ever, this is a working hypothesis, not a work of reference.

From the NMR, York

The memorial contains a tablet inscribed with a text of gravity and pathos appropriate to the time. The present tablet is a copy of one vandalised in 1990 and replaced in 2001. There is a second copy at Newton-le-Willows railway station (shown above) and the vandalised version, suitably restored, is now in the National Railway Museum at York. However, that is not the original tablet.

The original tablet was placed at Parkside in May 1831 but there is no mention of this in the standard texts although its presence is recorded without details in a memoir on Huskisson published in 1831. Given its location it was presumably a mark of respect paid by the railway company on behalf of its staff, directors and shareholders. Huskisson played a pivotal role in guiding the enabling legislation through Parliament which made his death on the opening day doubly tragic.

The author of the single, very long sentence on the tablet is unknown. A printed copy is among the papers of director Charles Lawrence relating to Huskisson and there may be further information in that archive.

However, this first tablet was destroyed in the winter of 1837/8 due to frost damage causing the bank to which it was fixed to press heavily against it. It would seem therefore that the tablet at that time was fixed directly to the rock of the embankment. The railway company funded a replacement in 1838. Roscoe’s 1839 Book of the Grand Junction Railway mentions “a marble slab fixed in the wall at this station is the sad memorial of it”.

Measom’s 1859 Illustrated Guide to the Northwestern Railway mentions a monument to Huskisson at Parkside but gives no details.

We next hear of the tablet in a report dated September 14 1880 in the Manchester Guardian which describes the tablet as being “between two buttresses that support an iron water tank”. This does not sound like a classical temple in miniature. Rather, the buttresses may have been the buildings housing the watering station, probably a boiler and an engine for pumping. Maps suggest the structure may have been largely intact in the 1880s but to have shrunk to something like its present dimensions by the 1920s.

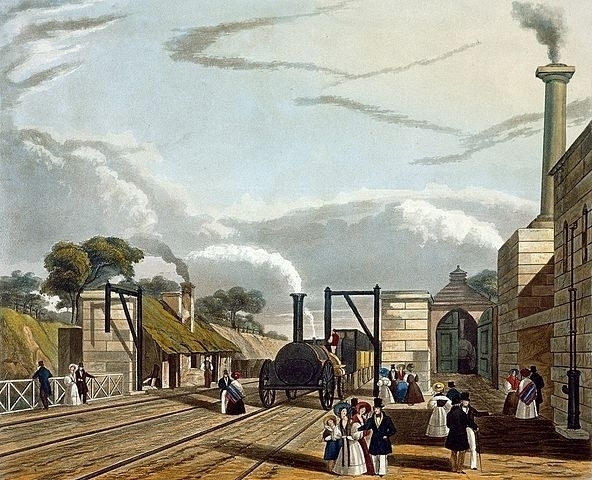

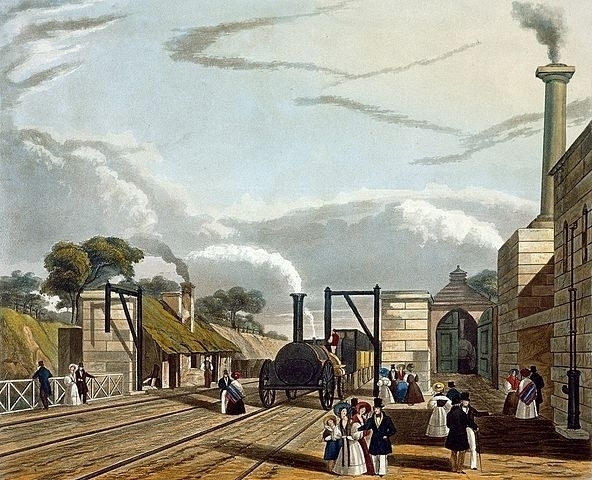

By Thomas Talbot Bury (excerpt)

The structure features in two editions of a print by Thomas Talbot Bury that are distinguished by the presence of a chimney on the eastern block and a shed for a relief locomotive just beyond. In both editions the gap between the two end blocks (or buttresses) is mostly rock with just a single course of stone. Indeed, three people can be seen in front of the putative tablet location as if looking at it. An 1837 edition of a guidebook to the Grand Junction Railway (which ran from Birmingham and thence to Liverpool and Manchester on L&MR track) suggested that there was also a rail that pointed to the exact spot where the accident occurred.

The structure can also be seen under construction in a sketch by Isaac Shaw as well as in his print of a goods train. In the former case we can see a plausible water tank on the ground with probable stonework in place of much of Bury’s rock (which might, however, be obscured). The print of the goods train shows the structure in an earlier guise without a chimney, the mid-region still largely masonry (but again part-obscured), and the water tank now raised into position.

By Isaac Shaw (excerpt)

It seems feasible therefore that the tablet was fixed first to the rock and then in 1838, slightly higher, to the masonry. The 7-month delay in mounting the tablet in the first place may then be ascribed to the construction of the watering station during 1831. The somewhat peculiar incorporation of the rock into the watering station may have been for reasons of economy. Alternatively, it may have been intended as part of the setting for the memorial tablet, possibly referencing the much cruder station of the tragic opening day. The use of stone facings (if such they were) seems to accord the watering station a higher status than might otherwise be merited although trains did, of course, pause here.

Intermediate watering stations became less of an issue as technology developed and for long distance routes water troughs were provided between the lines as at Eccles. The station itself closed to passengers in 1839 when a second station opened at a nearby junction with the Wigan branchline, the original facility continuing for some years as a goods station.

The only direct reference to the tablet from around this time comes in the LNWR guide of 1894 which briefly mentions that the MP was commemorated by “a tablet on an adjoining wall”.

There is no indication that the original tablet was situated in a small temple and when this was added is unclear although I suspect others will know. Wikipedia has a photograph (above) showing a ceremony in front of the structure substantially as we see it today. This may have marked a rebuilding around part or all the water tank given that the tablet is now fixed to a metallic surface in an appropriate position. Note the rock face still present at track level. The date for this new development can only be judged on the basis of the image labels, 1913 seeming not unlikely given the dress of those present at the ceremony and the photographic equipment to hand. Perhaps an additional incentive behind the redevelopment was the need to remove dilapidated and unsafe old buildings or to close the goods station.

As mentioned previously, the memorial briefly hit the headlines when the (second) tablet was vandalised. While it features occasionally on TV (recently, for example, on Dan Snow’s railway history series), it seems to be very difficult to view except from a stationary train.

The three suggested locations for the tablet with the temple of 1913 added to the buildings of the 1880s and earlier.

In the 1880s it is possible that the buildings of the watering station were still present even if no longer used. Maps suggest that the engine shed formerly east of the watering station is now to the west with a possible goods shed occupying its original location. There is an additional building abutting the east flank of the boiler house, presumably the reason for the asymmetric nature of the low brick walls that encompass the contemporary memorial.

Huskisson’s death cast a shadow over the opening day and understandably dominated coverage in the newspapers. Although permission was reluctantly granted to inter Huskisson’s remains in Liverpool (his home was in Chichester), the mausoleum by John Foster Jnr in St James’s Cemetery was not finished until 1834. While it doubtless contributed to the public subscription for the mausoleum, the company may have felt it was appropriate to make a gesture of its own in the meantime once the watering station was in place. The provenance of the miniature temple remains obscure and surprisingly unremarked given its more recent origin.

I first wrote this account in 2017 on the build2understand blog on Silvrback under the nom de plume ed3d. This version has not been further updated as yet. The markdown support also varies between platforms so there may be issues that need fixing. Please bear with me.

On the opening day of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway in September 1830 there was a special running of eight trains to and from Manchester with the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, in a train pulled by the locomotive Northumbrian. This was the newest engine and ran on the southern track so that it could stop at will and also act as a static base for review of the other trains as they passed. Unfortunately the stop at Parkside to review and water the engines was marked by a severe and ultimately fatal injury to William Huskisson MP when he was knocked down and run over by Rocket.

For an event that commanded national attention there is a surprising degree of uncertainty about aspects of the opening day so the posting of a partial passenger list in a blog by a SIM Manchester author is of some interest. The blog suggests that there is no indication of the train to which passengers were assigned (Thomas, 1980, provides a longer consolidated list but again without assignment). It is, however, headed “No.1” and with the Prime Minister among those listed it seems plausible that this is a list of those accompanying the Prime Minister in the ducal carriage.

Another intriguing feature is the numbering which, I would argue, may reflect a seating plan. Suggestive evidence for this is the otherwise arbitrary placing of Mrs Arbuthnot, Wellington’s close friend and confidante, adjacent to the Prime Minister in the list.

Moreover, the list as presented is divided into two halves, 1-24 and 25-40. Assuming the structure is replicated in the original document, this may reflect the seating provision in the ducal carriage. Those named in the first part of the list would be seated on four benches, six per bench, running round the sides of the coach and those named in the second seated on two ottomans running the length of the coach, eight per ottoman seated back-to-back.

Wellington can be seen acknowledging the crowd by raising his hat at the front of the red carriage on the left.

Various sources suggest that Wellington was situated at the front of the ducal carriage, presumably at the end of the ottoman. In Shaw’s sketch and print he can probably be identified as the individual at the front of the large 8-wheeler carriage who has a large nose and is raising his hat.

There is another useful constraint, namely that Huskisson and Wellington (who might reasonably be felt to harbour a mutual grudge), were unable to communicate directly until Huskisson debarked at Parkside and walked around to the front of the carriage. It may be that Shaw shows Huskisson as the man standing towards the rear of the train. It is notable how few of the 40 passengers Shaw manages to depict from the relatively acute angle and how the preponderence of those is female, almost as if he wanted the viewer to focus on the two males whose faces are readily visible.

Although the artist has truncated the train to focus on major points of interest (and this version is cropped further), the picture shows a significantly larger number of passengers with males mostly at the edges. The presence of a soldier by the (double) door suggests additional staff may have travelled in the ducal carriage as close protection.

The ducal carriage was primarily occupied by dignitaries, mostly aristocrats, ambassadors and politicians, with their wives and daughters sitting on the ottoman. In some early pictures the ottoman is in two halves and this arrangement is adopted here. A second print by an unknown, possibly amateur, artist gives a better feel for this arrangement with the duke (in the cloak) shown at the front, men primarily down the sides and women behind them on the central ottomans.

Untruncated version from Museum of Liverpool. The composition of the train accords with most descriptions apart from the additional wagon for the flag bearers. Unlike Shaw’s version, it suggests one rather than two smaller carriages for the directors. Given that some directors were in charge of other trains, seating for 20 in one carriage should have sufficed unless, as Shaw appears to suggest, they were accompanied.

Names in italics represent substitutes likely to have been present on the day. Ottomans shown with red background.

With the possible exceptions of Wellington and Mrs Arbuthnot, the positions are hypothetical and based solely on consecutive numbering. They do, however, position Mr Arbuthnot close to his wife (for propriety) and the Dacres, Belgraves, Salisburys, Huskissons, Delameres and Stanleys are either adjacent to or relatively close to family members. The concentration of women on the inside (the widowed Lady Glengall is an exception) may have reflected a wish to shield their clothes from smuts and cinders.

Assuming she remained seated at Parkside, Mrs Huskisson would not have seen the accident that took place on the other side of the carriage. Those seated by Wellington on the other side are primarily politicians. Lord Wilton’s proximity to Wellington may be due to his acting as a guide. Indeed, the proposed addition of Mrs Moss and Mrs Lawrence may have been intended to serve a similar purpose as well as fill gaps.

The identity of most of those present is clear with one exception, Miss Long (Thomas calls her Hon. Miss Long). One possibility is that she is a daughter of Hon. William Long Wellesley. At the time she would have been a ward of the duchess of Wellington so it is possible that she accompanied the duke though is seated here with young women of similar status.

Seating layout with a row of six bench seats down each half side and an ottoman in each half accommodating eight passengers sitting back-to-back.

A quick build suggests that the seating plan just about works based on 0.5x0.5 m per seat. Of course, those at the ends of the ottoman such as the duke can sit in either front-facing or sideways orientation. He can also make himself readily visible to crowds and passing trains.

While passing space in the aisles may be at a premium (as in a theatre), there are useful spaces at either end and the middle for socialising.

The radical lawyer-turned-Whig politician Henry Brougham, later Lord Brougham and Vaux, was a supporter of the 1825 Railway Bill and earlier in 1812 had stood unsuccessfully against Canning for one of the Liverpool seats in Parliament. An ardent supporter of technical education for the working and artisan classes, in 1825 he opened the Liverpool Mechanics' Institute which was supported by many of the L&MR directors.

His memoirs make it clear that he was hoping to talk to Huskisson at Liverpool about a possible return to politics in conjunction with William Lamb, Viscount Melbourne. Melbourne, however, was unable to attend the opening as he was recovering from an operation on a carbuncle.

As he was well known to the directors, it may be that Brougham travelled with them rather than in the ducal carriage.

Further research is required to compare the list with those who actually travelled on the day (some substitutions have already been made). The motivation underpinning any seating plan may be of interest if it reflects the wishes of the directors to promote the railway or reward its supporters. The preponderance of males around the circumference may, however, simply reflect a wish to protect female dresses from smuts and embers emitted by the engine.

Further understanding of the composition and arrangement of the passengers in this carriage may be assisted by analysis of published diaries. Such were the numbers of dignitaries travelling that day that their absence from the ducal carriage is also a subject of interest.

I first wrote this account in 2017 on the build2understand blog on Silvrback under the *nom de plume* ed3d. This version has not been further updated as yet. The markdown support also varies between platforms so there may be issues that need fixing. Please bear with me.

There are many accounts of events at Parkside that led to the death of Liverpool MP William Huskisson on the opening day of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway in 1830. They are typically incomplete or erroneous and there is no reason to suppose that this one is any different. However, it takes as its starting-point a different perspective, by no means original but commonly omitted, that only one engine out of the eight actually took on water at Parkside itself. I’ve updated this account after having read The Liverpool & Manchester Railway by RHG Thomas which adds some interesting sidelights. Please bear in mind that I draw largely but selectively from secondary sources.

Dr Joseph Pilkington Brandreth was a physician who worked at the Liverpool Dispensary on Church Street founded by his father to provide medical advice and treatment to the poor1. His brother Thomas was a solicitor and both brothers were listed as proprietors in the Railway’s enabling act. Thomas is probably best remembered, however, for his horse-driven entry to the Rainhill Trials, Cycloped. The two brothers lived next to one another at 43 and 45 Rodney Street.

Brandreth’s recollections were recorded in a letter to his sister Mary who had married the MP Benjamin Gaskell and now lived in Yorkshire.

Brandreth was in the last row of seats at the back of the leading train on the northern line which was drawn by the engine Phoenix. According to most reports (but not this one) it would have picked up coal and water at Parkside before moving away and waiting for the other trains to catchup.

Brandreth might be expected to make a good witness given his academic background and affiliation with the company. However, his testimony does not start too well as he gets the number of trains and passengers significantly wrong. To be fair, there are few accounts of that day that appear completely reliable.

Getting out of his carriage and climbing to the top of the cutting, Brandreth looked back and saw “two trains arrive, and stop at their purpose place” but the fourth (this number including Phoenix) remained beside the Duke’s carriage. This observation is odd because those two trains should have been drawn by North Star and Rocket which might (erroneously) suggest that it was the next engine, Dart, that was involved in the accident and hence stopped at Parkside.

Parkside by Thomas Talbot Bury

One point uncommonly made by Brandreth but confirmed by Rolt and Thomas among others concerns multiple “watering places”. Contrary to many accounts, most engines took on water and fuel at points distant from Parkside itself, presumably to speed matters up by using a parallel rather than serial approach. The details are unclear but we know that Phoenix was about 880 yards from Parkside and that Rocket should have been at 440 yards which suggests that the interval being used was 220 yards and that North Star and Dart were therefore scheduled to halt at 660 and 220 yards past Parkside respectively. If no train was scheduled for Parkside itself (it would have entailed unseemly proximity to the ducal train), then Comet would have been at -220, Arrow at -440 and Meteor at -660 yards.

At a total of 1540 yards, this is patently much less than the 1.5 mile (2640 yard) distribution cited by Rolt who implies an interval of 440 yards. This might suggest that the interval is either incorrect or variable.

However, if four trains with an interval of 220 yards were stationed beyond Parkside and three with an interval of 440 yards before it, the last train would be rather handily stopped at Newton-le-Willows and the total distance would be 1.25 miles or 2200 yards. In that case a delay between the fourth and fifth trains would be expected and the egress of the passengers might have reflected a miscalculation or misapprehension on their part as to when the delay was likely to occur.

A further possibility is that the last four trains would use the same locations as those presently occupied beyond Parkside, the three leading trains starting out as soon as the fourth arrived in place, the latter shuffling up to the position occupied by Phoenix before starting to take on water. This strategy would seem to allow better continuity for the review at Parkside.

The parade was subject to review by the ducal train first at Rainhill and now at Parkside. This piece of theatre was for the entertainment both of the other passengers desirous of seeing the ducal train and, of course, the myriad spectators, many of whom had paid for a seat in a grandstand. Several journals mention that not only did the trains pass by slowly but that they also reversed and ran past again, doubtless with the intention of providing a more prolonged spectacle for the crowds. This latter manoeuvre does not appear in the orders to engine men and likely reflects high spirits on the day among the engineers acting as train directors. It must, however, have been a major concern for the policemen managing traffic in the two stopping places.

The overall context, that this was a review, explains why Rocket was seeking to run through the station, albeit slowly, rather than stopping, its “watering-place” being on the far side. The fact that ultimately it did pass through with minimal delay is explained simply by the need to make space to recover Huskisson once he was removed from the track. Dart, the next engine, was presumably halted short of the accident site, policemen with speaking-trumpets having run back up the line to warn oncoming trains which would have had to run on some distance both to brake safely and to avoid collision.

Coincidentally, there have been a couple of claims made against Dart (controlled by Gooch) as recounted by Ferneyhough 2, including the entry for Huskisson in the Dictionary of National Biography. The scenario presented here might give some basis for a possible misunderstanding.

Fearing the delay to the fourth train (Dart) indicated some serious incident, Brandreth left Phoenix and began to walk towards Parkside only to be met by a Mr Forsyth (presumably Thomas Forsyth, another of the early proprietors) who had run to fetch him. Together they returned to Parkside where Brandreth found the mortally injured Huskisson on a door (as makeshift stretcher) being treated by the Earl of Wilton who had applied a tourniquet to the leg (Wilton was not medically qualified but had a considerable interest in anatomy). Wilton would be the main witness at the hastily convened inquest the next day at which the company was completely exonerated.

We now turn to earlier events prior to arriving at Parkside and then at Parkside itself.

William Huskisson was not the first railway fatality but he is probably remembered as the most prominent. He became one of Liverpool’s two MPs in 1823 and did much to promote the cause of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway in Parliament despite coming from the landed classes and having an interest in the canals. A moderate Tory, he had held a number of significant government positions including President of the Board of Trade but tendered his resignation from government in 1828 when the Lords blocked electoral reform. According to Huskisson, the ultra-Tory Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, was not supposed to accept the resignation but to use it as a bargaining chip with the Lords. It was not to be and his departure from government was arguably a significant loss. While possessing no great oratorical skills and, indeed, being somewhat reserved if amiable, Huskisson was an astute politician who reflected the spirit of the times in much better fashion than the deeply unpopular Wellington. Severe illness in August 1830 meant that Huskisson was incapable of fighting his seat in person in the election but he was in any case returned safely through the machinations of his Liverpool supporters. He received a rapturous welcome when he subsequently visited the Liverpool Exchange in advance of the railway’s opening.

The principal guest, however, was the Duke of Wellington who came to Liverpool to open the Railway on 15th September 1830. Together with more than 700 guests he undertook the inaugural 31 mile rail journey from Liverpool to Manchester.

Wellington’s ornate ducal carriage and associated cars were being pulled by the powerful steam engine Northumbrian under the control of Principal Engineer George Stephenson. The ducal train ran freely on the southern line while the remaining seven trains used the adjacent northern one. This meant that the VIP train under Stephenson’s supervision could vary its speed, review the other trains so their passengers could see the Duke and pause at features of special interest without impeding traffic on the adjacent line. I suspect it also gave Stephenson the opportunity to liaise with the other drivers and would facilitate the rapid extraction of the VIPs in case of need. As we have seen, the trains on the northern line were supposedly separated by about 200 yards, a relatively short distance if one remembers that a train travelling at 15 mph covers 220 yards in 30 seconds.

The engines necessarily stopped to take on water and replenish fuel at Parkside, the halfway point, passengers having been specifically asked not to get out of the carriages during this wait. Although the proceedings thus far had not been without incident3, the Directors must have been feeling a certain degree of elation that things had passed off so well and perhaps they dropped their guard. Again, as had earlier occurred at Rainhill, there was an opportunity for the Duke to acknowledge the passengers in the other trains once more as they slowly ran past the ducal train, albeit largely for the benefit of the doubtless considerable crowds. This was, after all, to some extent a repeat performance.

Politically the Duke may have seen the ceremonial aspect of the journey, the parades at Rainhill and Parkside, as an opportunity to impress on both locals and national newspapers his support for some of the country’s most powerful technologists and “merchant princes”. The entirely positive response he was receiving from the crowds in and beyond Liverpool must have been some vindication. The railway company would in turn be hoping for some implicit endorsement of their product, reflected lustre and a positive review for subsequent projects.

Northumbian was first to Parkside and then saw Phoenix and North Star slow and pass through to their watering-places. Rocket was due next. However, one after another acccompanying dignitaries began to dismount from the train and to stretch their legs at Parkside while they waited for their engine to be serviced and the others to pass.

Estimates of the number of passengers dismounting vary; some say around 15 (at least, initially), others 50 (the ducal train had one or two additional VIP carriages carrying Directors and their guests as well as a car for the band). The men were reportedly mingling and chatting, doubtless in high spirits and looking to the future. The women stayed onboard, either following instructions or because of the absence of steps from the carriage. The policemen apparently attempted to persuade passengers to return to their seats but were in an awkward position given the presence of their superiors. In any event, they were likely significantly distracted from monitoring other areas.

The layout of Parkside is reasonably well-documented by the works of Bury and Shaw, the two artists most associated with the early days of the railway. Parkside was located in a relatively shallow but steep-sided cutting with, on the north side, small water reservoirs behind a fence (referred to as “pools” or “puddles” in some descriptions). Contemporary accounts, however, suggest that the reservoir was at that time in the process of excavation and some 15 feet deep. There are some suggestions that the hut seen in many pictures was added in 1831 although the door that later served as a stretcher was expropriated from one of the nearby company “hovels” so buildings were present, either associated with railway construction or for use as stores. Presumably the steep slope of the cutting extended a little further towards the excavation if the hut was absent. The picture shows water cranes opposite one another on either side of the track and on the southern side a boiler and steam engine to pump pre-heated water to them.

(Update 13/09/17) Bury’s picture shows a relatively mature Parkside layout with the addition of a shed for a spare engine not seen in the first version. However, the rather dishevelled hut shown may have been replaced by 1834 (possibly in 1831) with a much nicer single-storey building with a hipped roof and a dropped-edge hood moulding over the window, a motif common to several of the company’s works (there is an image in the catalogue to the London exhibition termed The Padorama). However, Thomas includes a sketch map by EJ Littleton that suggests a far more primitive layout at the time of the opening with water on both sides of the track rather than solely behind the fence to the left. In that case there were probably no boiler, engine or water cranes although these must have been built soon after to have appeared in Shaw and Bury’s prints. The suggestion is that stone had been quarried on both sides of the track and the ravines thus created had both filled with water.

We know little of the crowds present from nearby towns and villages but the bridge closeby and the fields above the cutting would both have formed natural grandstands close to trains and VIPs alike. The intervals between the passage of trains would be filled by music played by the band accompanying the ducal train. We know that there were also significant crowds at Eccles where the injured Huskisson would later be taken and some have suggested that the crowd at Parkside gave first warning of the imminent arrival of Rocket some 200 yards away.

All the engines were under the command of one of the senior engineers although it seems likely that there were regular drivers in attendance as well. Joseph Locke was in charge of the Rocket but Thomas identifies Mark Wakefield as driver and Adam Hodgson as Director of the train. He also names two brakesmen; although the engine may have lacked brakes, presumably some of the carriages did not. The firemen are not identified for any train and also notably unnamed for Rocket only is the flagman. Altogether, the picture emerges of a busy footplate with some potential conflicts of responsibility. Indeed, there are (marginally fanciful) pictures showing Northumbrian with up to seven people, most in top hats, crammed onto the tender and footplate on the opening run.

(Update 13/09/17) Thomas includes a copy of Stephenson’s instructions to “engine men” that requires they carry three flags: white (meaning “go on”), red (“go slowly”) and purple (“stop”). Presumably these were intended for dismounted guards to communicate with other trains in the event of a derailment or similar incident. However, there was also a signal flag carried by the train (possibly by the guard) which when upright indicated that the train carrying it should proceed and if horizontal “must be considered a signal for the next engine to fall back or come forward, as may be required”, a somewhat disconcerting ambiguity.

Rocket was pulling the third train on the northern track. Although winner of the Rainhill Trials the previous year, it was now relatively elderly and, although heavily modified, out-classed by more recent designs. Accordingly, it was pulling a shorter train and was running late into Parkside. It seems not unlikely that it would have slowed in particular on the ascent of the Whiston incline, doubtless slowing the trains behind as well.

(Update 13/09/17) Rocket may also have been delayed by the derailing involving Phoenix and the subsequent minor collision with the following train worked by North Star. The location is not stated but distances between trains were supposed to be 100 yards at slow speeds and 200 yards above 12 mph. Given the collision, the distances were clearly the bare minimum and arguably inadequate.

Huskisson had most likely been travelling towards the rear of the ducal carriage and sat separately from both his wife, the latter joining a group of other women, and Wellington. After dismounting at Parkside, he chatted with Director Joseph Sandars and, possibly at the bidding of Chief Whip William Holmes MP, had shaken hands with Wellington, either to be civil or, according to others, to start some kind of rapprochement. Wellington was seated at the forward end of the ducal carriage and to one side, presumably at this stage the side nearest the passing trains he would be expected to acknowledge. Whether Sandars had debarked simply to chat or to encourage a return to the carriages is unclear. Doubtless policemen would be reluctant to enforce company policy if a Director was among those on or between the tracks. It is worth mentioning that the surface of the permanent way would have been close to the level of the rail and there were no sleepers to trip over.

The ducal carriage was sandwiched between two cars for the use of the Directors, their guests and lesser notables and preceded by the band wagon (which is presumably not counted in the sum of three carriages officially drawn by Northumbrian) and tender.

The ducal carriage was 32 feet long and 8 feet wide with 8 wheels. It had only one entrance on each side and lacked built-in steps, a staircase intended for the benefit of lady passengers being hooked up at the rear and not deployed (presumably the dignitaries jumped or lowered themselves down to exit at Parkside). It would be challenging for Huskisson to gain entry without the assistance of those steps.

Huskisson had suffered a strangury at the recent funeral of George IV and the remedial surgery by Copeland had paralysed one leg and numbed part of the other. His attendance at the railway’s opening had therefore been in considerable doubt. Walking would have been difficult for him but doubtless lifted by the occasion and proud of the achievements of his constituents, he was determined to participate.

It is hard to imagine what the passengers who descended onto the track had in mind. Having seen Phoenix and North Star pass through, they must have been aware that the majority of trains had yet to arrive and certainly those adjacent to the northern track will have seen how close was the approach of the passing train. They must also have gathered that the other engines were in fact being watered elsewhere. Parkside was a replenishment stop only for Northumbrian.

Walking on the track had been encouraged at some of the “open house” company events held to popularise the railway and it is possible the dignitaries could see passengers disembarking from the stationary North Star and Phoenix further up the line. Those with seats facing trackside (the seating for 30 ran down the middle of the ducal carriage) may have wished to have a better view, dismounted on that side and walked round the engine only dimly aware of the safety issues. Some of the elderly gentlemen, not least Huskisson at 60, may also have sought the opportunity for a “comfort stop”. Finally, it is also possible that Rocket’s late running had been noted by those on Northumbrian earlier. These were men who had made careers and fortunes from their ability to establish a relationship at a propitious moment that would later lead to a deal. Perhaps this was too good a chance to miss.

According to Edward Littleton, the Duke terminated the conversation with Huskisson with the words “Well we seem to be preparing to go on - I think you had better get in”. This erroneous statement was presumably precipitated by excitement in the crowd due to the imminent arrival of Rocket, then some 200 yards distant and presumably slowing for the review as it passed the ducal carriage. This may have precipitated the first movement towards the carriages as a means of escape rather than departure as the Duke surmised, unable to see Rocket.

If one assumes that the alert was given at 220 yards and Rocket was travelling at 15 mph then there was an interval of 30 seconds between alarm and impact. Of course, Rocket was most likely already slowing for review so the interval may have been nearer 60 or 90 seconds, sufficient time to consider multiple options.

Huskisson was presumably aware that Rocket was not scheduled to stop. His first reaction would doubtless have been to follow Wellington’s advice and clamber aboard the ducal carriage via the door midway along and in the direction of the oncoming Rocket. In the absence of the deployable stairs the 38 year-old Edward Littleton did this with no little difficulty and then pulled Prince Esterhazy up after him. Holmes was also in the vicinity, possibly with one other, and Huskisson may have decided that being at the back of this apparent queue was not the best option for him.

There are suggestions that Huskisson crossed the adjacent track with a view to harbouring there or clambering up the bank but the presence of the excavations may have limited the available space to climb.

One can roughly estimate the likely minimum overall width of the railway cutting by looking at aerial photos of the Sankey and Newton viaducts which are both about 24 feet across. We know that the distance between the rails was standard gauge, 4 feet 8.5 inches, and, indeed, that the ducal carriage was some 8 feet wide, implying an overhang on either side of about 20 inches. The width of Rocket’s train is unclear (several different types of carriage were in use that day) though the overhang was probably much less (some say just 6 inches). However, if we assume it is also 8 feet and the clearance 18 inches, then the clear space at the trackside would be at least 3 feet 3 inches, probably more. This would certainly have been sufficient to accommodate Huskisson if he crossed the track although whether he was in a position to make that judgement is unclear. The presence of the excavated pit and associated works, fence, etc may have complicated matters and we do not know to what extent any space was already occupied by passengers and local dignitaries..

The distance between the two middle rails, sometimes called the “six foot”, is contentious with estimates ranging from 4 feet to standard gauge, the attractive but possibly apocryphal idea being that wide loads could be carried down the centre pair of rails. It is not especially relevant to the discussion here.

There may also have been a subliminal concern for Huskisson that he would miss the departure of the Northumbrian with his wife onboard if it were indeed leaving.

Huskisson perhaps then crossed back to the ducal carriage and attempted to clamber aboard. The Chief Whip William Holmes MP called on Huskisson to do the same as him, namely to press his back against the carriage so as to fit into the 18 inch clear zone. Huskisson may have decided that his bulk would count against him. Holmes also had a singularly dubious reputation and had been no friend of the Huskissonites in Parliament (Moss had been concerned about his involvement in piloting the railway bill past the hostile Lords). For whatever reason, on the spur of the moment Huskisson may have felt viscerally disinclined to take his advice.

What happened next is unclear. In his statement to the inquest Wilton said that Huskisson was attempting to move around the carriage door, presumably to get to the entrance, but became entangled with it. His problem with his legs was compounded by a weakness in one arm which had previously been broken three times. By now the locomotive would have reversed gear and was braking to a halt albeit too late to help Huskisson. It collided with the carriage door, knocked part of it off and dislodged Huskisson whose leg fell across the track and under the wheels.

Huskisson would be dead by the day’s end and Wellington’s ministry would outlive him by a mere two months

I first wrote this account in 2017 on the build2understand blog on Silvrback under the *nom de plume* ed3d. This version has not been further updated as yet. The markdown support also varies between platforms so there may be issues that need fixing. Please bear with me.

There is even more conjecture here than normal. Many accounts written at the time and since are partial, evasive or both, Rolt being an exception in his biography of the Stephensons which, like this post, derives somewhat from a collection of anecdotes and reportage.

For those playing catch-up: Part 1, Part 2.

As a reminder, the ducal train was on the southern track pulled by Northumbrian. The seven trains on the northern track running into Manchester Liverpool Road station were drawn by Phoenix, North Star, Rocket, Dart, Comet, Arrow and Meteor and were pulling a total of 24 carriages.

For the passengers on the eight trains making up the inaugural procession on the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, the severe injury to Huskisson and a change in the weather had dampened spirits and more. The crowd waiting for the trains to pull into Manchester extended some four miles up the line and was by no means entirely welcoming. Progress was slowed by track incursions that incidentally threw wet sand over the carefully cleaned tracks. The 59th Regiment were in attendance in addition to the railway and civil policemen but the crowd was immense and contained unruly elements.

The people of Manchester had multiple issues with the ultra-Tory Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, including electoral reform (Manchester returned no MPs at this time and the franchise generally was limited) and concern over the railway taking jobs from other transport sectors such as canals and coaching. The living and working conditions of those employed in mills and mines were poor and the owners frequently exploitative. As we have seen, there was also a history of dissent being repressed by violent means. Some among the crowd chose to express their discontent vocally, by holding-up banners and placards, by wearing revolutionary cockades (thoughtfully provided gratis by a local newspaper) and by throwing stones. The atmosphere was very different from Liverpool and doubtless exactly what the Duke had feared.

The arrival of the procession was signalled by the firing of a cannon, the sound being heard by the mortally injured Huskisson at Eccles some 4-5 miles away. As the engines were due to be serviced again there later, this may have been as much a signal as ceremonial although it provoked Huskisson to express concern for the Duke’s safety. For the crowd near the station it might have been perceived as a starting pistol.

Many who had come to see the trains would have been just plain curious and hoping for a sight of the famous Duke above all else, something they could tell their children and grandchildren about in years to come. The extent of the crowd, however, meant that police and military cordons became severely over-stretched and as a consequence the crowd surged through and accessed locations supposedly off-limits such as the track and station.